Artist or rural activist? The idea of labels does not hold any appeal for Varanasi-based Umesh Singh. He draws from his childhood experience of tilling fields in his ancestral village, Kurmurhi, in Bhojpur, Bihar.

A research scholar at BHU, Singh is studying ecological art practices in India. His art focuses on social issues–casteism, environmental concerns, and rural struggles. As he probes the effect of urbanisation on rural life, his sculptures, drawings, and installations reflect his concerns about the fading legacy of farming cultures, the disappearance of seed varieties, and migration to bigger towns and cities.

I don’t define myself strictly as an artist or activist–I do what feels right. As an artist, I use my work to raise awareness about important rural issues.

Also read: He’s saving Tripura’s puppetry tradition, no strings attached!

Issues that raise questions

He says, “I work on various issues – farmers’ struggles, ecological imbalances, and environmental changes. For instance, our wells and handpumps have been drying up over the last few years. These small things are the lifeline for the poor. If these dry up, what will happen to our villages? Earlier, we could dig a pit and find water. Now, every summer, the water disappears.”

“The heat,” Singh adds, “is becoming unbearable. We’ve abandoned our traditional ways of building houses and started constructing box-like structures which trap heat like gas chambers.”

Collecting indigenous seeds is also slowly becoming a lost art. “Earlier, we saved our own seeds. The concept of the khalihaan or open granary has vanished. We use machines for harvesting. We have to buy seeds from the market now,” he explains.

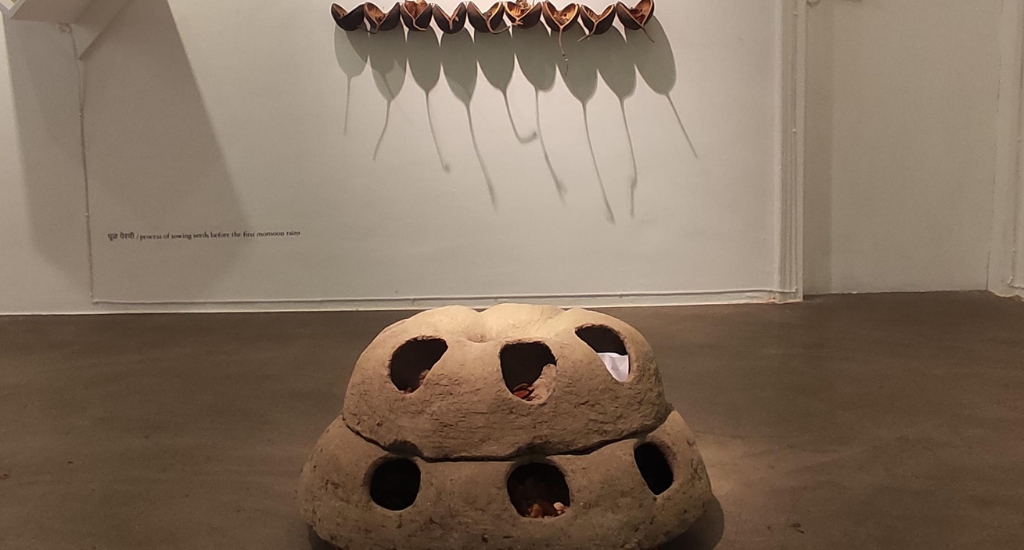

In fact, inspired by his mother’s seed preservation practices, he began collecting and studying seeds, recreating traditional handmade storehouses like kothila and bhaadi. For him, these coiled structures represent indigenous architectural wisdom and symbolise sustainability and continuity. He calls them knowledge keepers, as he attempts to “honour and sustain indigenous memory and agricultural traditions”.

The loss of indigenous knowledge is a concern for Singh. For instance, he says, “We used to create employment through these skills–cattle rearing, rope-making from plastic bags, and more. Charpoys were common in villages and my grandfather made ropes and other items, but he couldn’t earn from them. People would give him food in return, not money. Eventually, families abandoned these skills, seeking work outside the village for daily wages instead.”

Singh is now learning how to make ropes and hopes to teach it to others. “Self-reliance is crucial and indigenous knowledge empowers people directly. If you need a rope, you should be able to make it yourself.”

Also read: From waste to wonder – Odisha’s eco-friendly cow dung toys

Work that speaks

One of the Artists-in-Residence at India Art Fair Delhi 2025, he uniquely intertwines art and agriculture, incorporating forgotten farming tools, parasitic woods and materials. His current exhibition includes a Bhojpuri poem carved onto wood.

For one of his significant works, Uncomfortable Tools, showcased at the 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale when Singh was a student in Hyderabad, he merged farming tools with parasitic woods as a commentary on the relationship between utility and obsolescence in farming. Collecting tools from farmers who have abandoned farming, he replaced the handles with diseased wood to communicate distress and create ‘uncomfortable tools’ as a symbol of decay and destruction.

His other works include photographs of farmers and farm labourers wearing muzzles on their faces, similar to the “jaab” tied on oxen’s mouths to prevent them from grazing while working, as a symbol of subjugation. He says, “I crafted ox masks from hay ropes to symbolise their plight–working tirelessly yet receiving little in return, much like their cattle.”

Inspired by socially conscious artists like Ramkinkar Baij and Navjot Altaf, Singh tells the stories of marginalised communities, farmers and landless labourers. A multidisciplinary artist, his series of photographs (cyanotype prints) reflects his deep and abiding connection with his village and its people. He chooses to work with natural and sustainable materials, avoiding toxic chemicals like nitric acid, which harm the environment.

Many families in my area, who own very small plots of land, have abandoned farming,” he says. Organic farming and innovative methods are still to reach his village. “They have little land and the focus is on survival.”

His own family migrated to the city in search of better prospects. He recalls, “I grew up in the village, where life was simpler. I worked in the field, harvesting wheat, watering fields and climbing trees for mangoes.”

Finally, he says, “I don’t define myself strictly as an artist or activist–I do what feels right. As an artist, I use my work to raise awareness about important rural issues.”

Also read: A village tourism bucket list for art lovers

The lead photo shows a photograph of a performative art by Umesh Singh in progress, from 2019. (Photo courtesy Umesh Singh)

Anuradha Varma is a journalist and Mindset Coach. She hosts the podcast Swishing Mindsets.